Pterosaurs

Still Living

Does only one ropen live

continuously on Umboi Island?

Why the living-pterosaur expert Jonathan Whitcomb believes one ropen defends Umboi against other ropens

By Jonathan Whitcomb

I believe that at least a few giant ropens live in Papua New Guinea. So

why did I return to the United States, in 2004, proclaiming that only one

giant ropen lives on Umboi Island? I had several reasons, but I came

to the following conclusion: Only one ropen still flies regularly, at night,

over mountains and reefs of Umboi.

I do not imply that this species of living pterosaur, what some natives

call ropen, is in danger of extinction within the next few years. These

flying creatures, in all their species, are widespread across the planet.

Yet we need to do what we can to preserve them. The first step is in

learning more about them and publicizing the wonderful news that a

few species of pterosaurs are not extinct.

I have too many reports to allow me to fear pterosaur extinction. This

includes interviews several eyewitnesses of what seem to be gigantic

long-tailed pterosaurs in the southwest Pacific.

One report is from a couple who lived in Perth, Australia, in 1997.

Although the creature seen by this couple may be a different species

than the large ropen of Umboi, it is a giant with a long tail, apparently

lacking feathers, as does the nocturnal flying creature of Umboi. This

kind of animal is called by some people a "dragon."

Consider a pterosaur-like thing seen near Indonesia, in the southwest

Pacific, in June of 2008. Not long after the sighting, I got a phone call

from one of the two pilots: His small airplane almost collided with what

at first appeared to be another plane. But on passing it, the pilot who

was in control saw it flapping its wings, obviously a large flying creature.

As he and his co-pilot were approaching Bali, Indonesia, having taken

off from Broome, Australia, they were shocked to find themselves on

a collision course with something. He put his plane into a dive to avoid

the collision but both men realized that they had just missed a non-plane.

Right away they came up with the same word: "pterodactyl," another

shock. After my interviews with the men, they decided to avoid labeling

what they had seen as a "ropen," at least on the record. Still, they did

notice a few things that made them doubt that it was any common bird.

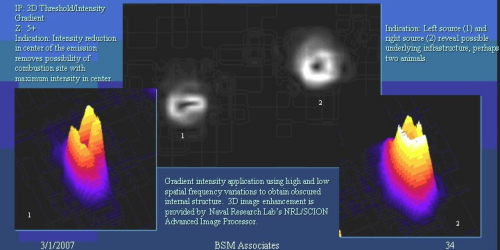

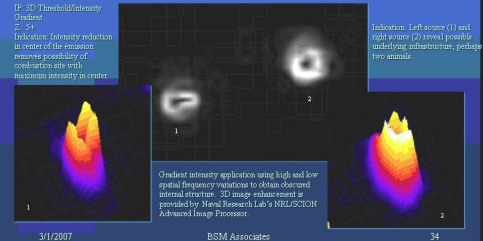

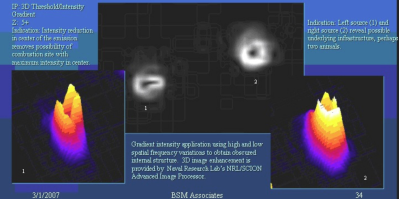

Indava lights videotaped by Paul Nation in Papua New Guinea

in 2006 (likely bioluminescence of flying creatures related to the ropen)

image copyright 2004 Jonathan Whitcomb

Mount Sual, as seen from the front porch of Mark and Delilah Kau's house near

Gomlongon Village, Umboi Island, Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea. This is

one of the mountains where the ropen is seen. This image is taken from a video

recorded by Jonathan Whitcomb during his 2004 expedition on Umboi Island.

Is it just one ropen on Umboi Island?

Yet with all that said, why would only one ropen live on Umboi Island?

The gigantic long-tailed featherless flying creature seen over Perth,

Australia, in 1997—that one appeared to be alone, as did the apparent

“pterodactyl” that was, at first, mistaken for a plane near Indonesia. We

have more direct circumstantial evidence, however, on Umboi.

The two expeditions of 2004 (the first led by me, Jonathan Whitcomb,

and the second by Garth Guessman and David Woetzel) led us to be-

lieve that at least a few hundred villagers have seen the ropen's light at

least once in their human life spans. But all the reports of which we are

aware were of a single glow, never more than one flying light at a time.

What is more, we have additional indirect evidence suggesting that the

gigantic animals, described like pterosaurs in the southwest Pacific, are

seen flying as individuals. Besides the sighting by the couple at Perth

and the sighting by two former marine pilots, who saw only one over the

sea near the island of Bali in 2008, we have similar encounters by other

eyewitnesses in this area of the planet.

The American Duane Hodgkinson saw only one huge “pterodactyl” in

New Guinea in 1944 near Finschhafen, and Brian Hennessy saw only

one large flying creature in New Guinea in 1971 on Bougainville Island,

and seven native boys saw only one at Lake Pung around December

of 1993 on Umboi Island.

There are exceptions to the lonely-ropen rule. Late in 2006, deep in the

interior of the mainland of Papua New Guinea, Paul Nation videotaped

two indava lights. In addition, I’ve read of reports of multiple-creatures,

pterosaur-like, flying in daylight. But each such report I can answer with

many reports of one creature, especially the largest ones. Uncommon

exceptions confirm the general rule.

Giant flying creatures that modern Westerners would call pterosaurs—

those may be the descendants of what were called, in old times and in

many areas of the planet, “dragons.” From historical records and the

traditions of people in South America, North America, and Europe, they

were solitary creatures, spending much of their time on top of cliffs or

on mountains overlooking water. I admit that this fact is but secondary

evidence: The many modern sightings, of a lone flying light or one flying

creature, on Umboi Island—that is more important evidence.

The American explorers David Woetzel (top, second from right) and Garth Guessman

(lower right) met many natives on Umboi Island and conducted a number of well-

prepared interviews. The islander Jonathan Ragu described the creature he had

seen flying near the coast in July of 2004. It was a lone ropen and Ragu chose

the Sordes pilosus, from among dozens of sketches the Americans showed him

of birds, bats, and pterosaurs. Woetzel and Guessman also interviewed Jonah Jim,

who had a sighting in 2001, in which the ropen flew towards Lake Pung. This native

also chose the Sordes pilosus, without knowing what sketch Ragu had chosen.

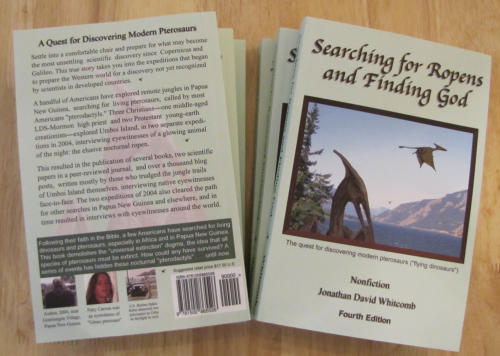

Searching for Ropens and Finding God may be the first book written specifically

about living pterosaurs observed worldwide. This nonfiction is by the American

cryptozoologist Jonathan David Whitcomb, and it is now in its fourth edition.

The “pterodactyl” observed in the mid-twentieth

century in Cuba (above) may be related to the

ropen of Umboi Island, Papua New Guinea

copyright 2005-2017 Jonathan Whitcomb

Duane Hodgkinson, in 1944, saw what he called a "pterodactyl" that flew

up from a clearing near the city of Finschhafen (on mainland of what's now

called Papua New Guinea). The wingspan of the creature he estimated to

be similar to that of a Piper Tri-Pacer airplane: about twenty-nine feet.

Jonathan Whitcomb has concluded that the ropen of Umboi defends that island and the surrounding reefs, as its territory, from other competing ropens

Pterosaurs

Still Living

Does only one ropen live

continuously on Umboi Island?

Why the living-pterosaur expert Jonathan Whitcomb believes

one ropen defends Umboi against other ropens

Indava lights videotaped by Paul Nation in Papua New Guinea

in 2006 (likely bioluminescence of flying creatures related to the ropen)

By Jonathan Whitcomb

I believe that at least a few giant ropens live in Papua New Guinea. So

why did I return to the United States, in 2004, proclaiming that only one

giant ropen lives on Umboi Island? I had several reasons, but I came

to the following conclusion: Only one ropen still flies regularly, at night,

over mountains and reefs of Umboi.

I do not imply that this species of living pterosaur, what some natives

call ropen, is in danger of extinction within the next few years. These

flying creatures, in all their species, are widespread across the planet.

Yet we need to do what we can to preserve them. The first step is in

learning more about them and publicizing the wonderful news that a

few species of pterosaurs are not extinct.

I have too many reports to allow me to fear pterosaur extinction. This

includes interviews several eyewitnesses of what seem to be gigantic

long-tailed pterosaurs in the southwest Pacific.

One report is from a couple who lived in Perth, Australia, in 1997.

Although the creature seen by this couple may be a different species

than the large ropen of Umboi, it is a giant with a long tail, apparently

lacking feathers, as does the nocturnal flying creature of Umboi. This

kind of animal is called by some people a "dragon."

Consider a pterosaur-like thing seen near Indonesia, in the southwest

Pacific, in June of 2008. Not long after the sighting, I got a phone call

from one of the two pilots: His small airplane almost collided with what

at first appeared to be another plane. But on passing it, the pilot who

was in control saw it flapping its wings, obviously a large flying creature.

As he and his co-pilot were approaching Bali, Indonesia, having taken

off from Broome, Australia, they were shocked to find themselves on

a collision course with something. He put his plane into a dive to avoid

the collision but both men realized that they had just missed a non-plane.

Right away they came up with the same word: "pterodactyl," another

shock. After my interviews with the men, they decided to avoid labeling

what they had seen as a "ropen," at least on the record. Still, they did

notice a few things that made them doubt that it was any common bird.

image copyright 2004 Jonathan Whitcomb

Mount Sual, as seen from the front porch of Mark and Delilah Kau's house near

Gomlongon Village, Umboi Island, Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea. This is

one of the mountains where the ropen is seen. This image is taken from a video

recorded by Jonathan Whitcomb during his 2004 expedition on Umboi Island.

Jonathan Whitcomb has concluded that the ropen of Umboi defends that

island and the surrounding reefs, as its territory, from other competing ropens

The American explorers David Woetzel (top, second from right) and Garth Guessman

(lower right) met many natives on Umboi Island and conducted a number of well-

prepared interviews. The islander Jonathan Ragu described the creature he had

seen flying near the coast in July of 2004. It was a lone ropen and Ragu chose

the Sordes pilosus, from among dozens of sketches the Americans showed him

of birds, bats, and pterosaurs. Woetzel and Guessman also interviewed Jonah Jim,

who had a sighting in 2001, in which the ropen flew towards Lake Pung. This native

also chose the Sordes pilosus, without knowing what sketch Ragu had chosen.

Is it just one ropen on Umboi Island?

Yet with all that said, why would only one ropen live on Umboi Island?

The gigantic long-tailed featherless flying creature seen over Perth,

Australia, in 1997—that one appeared to be alone, as did the apparent

“pterodactyl” that was, at first, mistaken for a plane near Indonesia. We

have more direct circumstantial evidence, however, on Umboi.

The two expeditions of 2004 (the first led by me, Jonathan Whitcomb,

and the second by Garth Guessman and David Woetzel) led us to be-

lieve that at least a few hundred villagers have seen the ropen's light at

least once in their human life spans. But all the reports of which we are

aware were of a single glow, never more than one flying light at a time.

What is more, we have additional indirect evidence suggesting that the

gigantic animals, described like pterosaurs in the southwest Pacific, are

seen flying as individuals. Besides the sighting by the couple at Perth

and the sighting by two former marine pilots, who saw only one over the

sea near the island of Bali in 2008, we have similar encounters by other

eyewitnesses in this area of the planet.

The American Duane Hodgkinson saw only one huge “pterodactyl” in

New Guinea in 1944 near Finschhafen, and Brian Hennessy saw only

one large flying creature in New Guinea in 1971 on Bougainville Island,

and seven native boys saw only one at Lake Pung around December

of 1993 on Umboi Island.

There are exceptions to the lonely-ropen rule. Late in 2006, deep in the

interior of the mainland of Papua New Guinea, Paul Nation videotaped

two indava lights. In addition, I’ve read of reports of multiple-creatures,

pterosaur-like, flying in daylight. But each such report I can answer with

many reports of one creature, especially the largest ones. Uncommon

exceptions confirm the general rule.

Giant flying creatures that modern Westerners would call pterosaurs—

those may be the descendants of what were called, in old times and in

many areas of the planet, “dragons.” From historical records and the

traditions of people in South America, North America, and Europe, they

were solitary creatures, spending much of their time on top of cliffs or

on mountains overlooking water. I admit that this fact is but secondary

evidence: The many modern sightings, of a lone flying light or one flying

creature, on Umboi Island—that is more important evidence.

Searching for Ropens and Finding God may be the first book written specifically

about living pterosaurs observed worldwide. This nonfiction is by the American

cryptozoologist Jonathan David Whitcomb, and it is now in its fourth edition.

The “pterodactyl” observed in the mid-twentieth

century in Cuba (above) may be related to the

ropen of Umboi Island, Papua New Guinea

Duane Hodgkinson, in 1944, saw what he called a "pterodactyl" that flew

up from a clearing near the city of Finschhafen (on mainland of what's now

called Papua New Guinea). The wingspan of the creature he estimated to

be similar to that of a Piper Tri-Pacer airplane: about twenty-nine feet.

copyright 2005-2017 Jonathan Whitcomb

Pterosaurs

Still Living

Does only one ropen live

continuously on Umboi Island?

Why the living-pterosaur expert Jonathan Whitcomb

believes one ropen defends Umboi against other ropens

Indava lights videotaped by Paul Nation in Papua New Guinea in

2006 (likely bioluminescence of flying creatures related to the ropen)

By Jonathan Whitcomb

I believe that at least a few giant ropens live in Papua New

Guinea. So why did I return to the United States, in 2004,

proclaiming that only one giant ropen lives on Umboi Island?

I had several reasons, but I came to the following conclusion:

Only one ropen still flies regularly, at night, over mountains

and reefs of Umboi.

I don’t imply that this species of living pterosaur, what some

natives call ropen, is in danger of extinction within the next

few years. These flying creatures, in all their species, are

widespread across the planet. Yet we need to do what we

can to preserve them. The first step is in learning more about

them and publicizing the wonderful news that a few species

of pterosaurs are not extinct.

I have too many reports to let me fear pterosaur extinction.

This includes interviews several eyewitnesses of what seem

to be gigantic long-tailed pterosaurs in the southwest Pacific.

One report is from a couple who lived in Perth, Australia, in

1997. Although the creature seen by this couple may be a

different species than the large ropen of Umboi, it is a giant

with a long tail, apparently lacking feathers, as does the

nocturnal flying creature of Umboi. This kind of animal is

called by some people a "dragon."

Consider a pterosaur-like thing seen near Indonesia, in the

southwest Pacific, in June of 2008. Soon after the sighting, I

got a phone call from one of the two pilots: His small airplane

almost collided with what at first appeared to be another

plane. But on passing it, the pilot who was in control saw it

flapping its wings, obviously a large flying creature.

As he and his co-pilot were approaching Bali, Indonesia,

having taken off from Broome, Australia, they were shocked

to find themselves on a collision course with something. He

put his plane into a dive to avoid the collision but both men

realized that they had just missed a non-plane. Right away

they came up with the same word: "pterodactyl," another

shock. After my interviews with the men, they decided to

avoid labeling what they had seen as a "ropen," at least on

the record. Still, they did notice a few things that made them

doubt that it was any common bird.

image copyright 2004 Jonathan Whitcomb

Mount Sual, as seen from the front porch of Mark and Delilah Kau's

house near Gomlongon Village, Umboi Island, Morobe Province,

Papua New Guinea. This is one of the mountains where the ropen

is seen. This image is taken from a video recorded by Jonathan

David Whitcomb during his 2004 expedition on Umboi Island.

Jonathan Whitcomb has concluded that the ropen

of Umboi defends that island and the surrounding

reefs, as its territory, from other competing ropens

The American explorers David Woetzel (top, second from right)

and Garth Guessman (lower right) met many natives on Umboi

Island and conducted a number of well-prepared interviews. The

islander Jonathan Ragu described the creature he had seen flying

near the coast in July of 2004. It was a lone ropen and Ragu chose

the Sordes pilosus, from among dozens of sketches the Americans

showed him of birds, bats, and pterosaurs. Woetzel and Guessman

also interviewed Jonah Jim, who had a sighting in 2001, in which the

ropen flew towards Lake Pung. This native also chose the Sordes

pilosus, without knowing what sketch Jonathan Ragu had chosen.

Is it just one ropen on Umboi Island?

Yet with all that said, why would only one ropen live on Umboi

Island? The gigantic long-tailed featherless flying creature seen

over Perth, Australia, in 1997—that one appeared to be alone,

as did the apparent “pterodactyl” that was, at first, mistaken for

a plane near Indonesia. We have more direct circumstantial

evidence, however, on Umboi.

The two expeditions of 2004 (the first led by me, Jonathan D.

Whitcomb, and the second by Garth Guessman and David

Woetzel) led us to believe that at least a few hundred villagers

have seen the ropen's light at least once in their human life

spans. But all the reports of which we are aware were of a

single glow, never more than one flying light at a time.

What is more, we have additional indirect evidence suggesting

that the gigantic animals, described like pterosaurs in the south-

west Pacific, are seen flying as individuals. Besides the sighting

by the couple at Perth and the sighting by two former marine

pilots, who saw only one over the sea near the island of Bali in

2008, we have similar encounters by other eyewitnesses in this

area of the planet.

The American soldier Duane Hodgkinson saw only one huge

“pterodactyl” in New Guinea in 1944 near Finschhafen, and

Brian Hennessy saw only one large flying creature in New

Guinea in 1971 on Bougainville Island, and seven native boys

saw only one at Lake Pung around December of 1993 on

Umboi Island.

There are exceptions to the lonely-ropen rule. Late in 2006,

deep in the interior of the mainland of Papua New Guinea,

Paul Nation videotaped two indava lights. In addition, I’ve read

of reports of multiple-creatures, pterosaur-like, flying in daylight.

But each such report I can answer with many reports of one

creature, especially the largest ones. Uncommon exceptions

confirm the general rule.

Giant flying creatures that many modern Westerners would call

pterosaurs—those may be the descendants of what were called,

in old times and in many areas of the planet, “dragons.” From

historical records and the traditions of people in South America,

North America, and Europe, they were solitary creatures, spend-

ing much of their time on cliffs or on mountains overlooking

water. I admit that this fact is but secondary evidence: The

many modern sightings, of a lone flying light or one flying

creature, on Umboi Island—that is more important evidence.

Searching for Ropens and Finding God may be the first

book written specifically about living pterosaurs observed

worldwide. This nonfiction was written by the American

cryptozoologist Jonathan Whitcomb (in its 4th edition).

The “pterodactyl” observed in the mid-twentieth

century in Cuba (above) may be related to the

ropen of Umboi Island, Papua New Guinea

Duane Hodgkinson, in 1944, saw what he called a "pterodactyl"

that flew up from a clearing near the city of Finschhafen (on the

mainland of what's now called Papua New Guinea). The wingspan

of the creature he estimated to be similar to that of a Piper

Tri-Pacer airplane: about twenty-nine feet.

copyright 2005-2017 Jonathan Whitcomb